A strong non-executive director (NED) I know, recently stepped down from the board of a large company after just six months. I was naturally very curious to understand the factors which led to this as I knew the non-executive director was quite excited about the company and joining the board and from what I understood, it looked like a very experienced board. When we discussed this, he indicated that at his third board meeting he realised that the CEO was dominating the board, that serious high quality challenge and debate was not welcome, NEDs wouldn’t be included in the upcoming strategy formation process and the board’s role was a de facto rubber-stamping body. In realising that he could not perform his role properly on behalf of shareholders, he felt he had no choice ethically but to step down. I asked him was there any way he could have realised this at the interview stage for the NED role and he responded that he asked a lot of searching questions of both the board chair and CEO – he was very comfortable about the responses. I also asked him if he shared his concerns with the board chair and other NEDs on the board prior to stepping down. He indicated that he did but disappointingly both the NEDs and the board chair acknowledged that the CEO was difficult to work with but business results were in general good, the NED fees were very competitive, shareholders were very happy with the CEO and that they “had learned to accept the status quo”. The iceberg analogy in the title of the article illustrates the point that while a board of directors may look strong on the surface, there is a lot of complexity and people factors underneath that can result in a quite a significant level of dysfunctional board types.

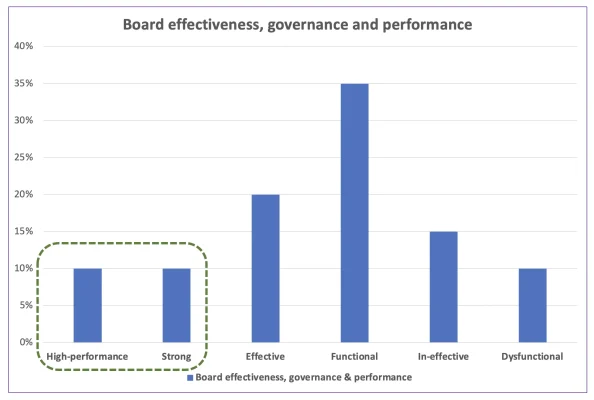

I have heard stories like this from many non-executive and executive board members over the years and it’s indicative of the very wide distribution of different board types that exist. In our work with board teams across Ireland, UK and internationally we see a very wide mix of board types and levels of board effectiveness and performance. Figure 1 below from our board best practices workshop illustrates our view on the distribution of board effectiveness and performance that combines both our own experience and our assessment of research in this area from around the world. A lot of board members and shareholders are pretty surprised to see that only 25% of boards are exceptional and strong with 35% being average and 40% of boards being in the mediocre and dysfunctional categories. What’s also important to say is that while it would be natural to think that boards of large companies and organisations with highly experienced executive and non-executive board directors would naturally be in the high-performing/strong categories, nothing could be further from the truth. Even within the boards of the largest companies and organisations, there is a very wide range of levels of board effectiveness and performance – excellence is not the default position of any board, no matter how large the organisation is and how experienced the executives and board directors are.If anything, some of the most complex dysfunction occurs on large organisation boards and some of these boards could give the plotlines and intrigue of “Game of Thrones” a run for their money !

We now focus on outlining the most common types of dysfunctional boards, their characteristics and the resulting problems for the organisation, its shareholders and stakeholders.

CEO-dominated board

This is quite a common board type where the CEO dominates the board and while on the surface it looks like there is a properly balanced board of executive and non-executive directors, in reality, it is the CEO that is the de facto decision-making entity on the board. Traditionally, these boards would be characterised by fire and brimstone CEOs who were not afraid to let everyone know who calls the shots on the board but as governance and board structures have become more sophisticated and shareholder tolerance for these types of behaviours have waned, CEOs are often a lot more subtle about this and as my NED colleague found out in the opening example, this may not be immediately obvious to prospective or new board members. The key characteristics of these types of boards are a serious lack of high quality robust challenge and debate, poor involvement by the NEDs in the strategy area and a greater potential for serious flaws in major decision making.In many of these boards, the board chairs and non-executive directors are hand-picked by the CEO and are very much expected to “toe the line” and effectively rubber-stamp the CEO’s recommendations and actions. In many cases, a board chair fundamentally enables this type of CEO behaviour whereby they are abdicating their responsibility to ensure a proper high-quality balanced board. The vast majority of high-calibre NEDs would either not join a board like this or would not stay long once they discover the true nature of the board. It’s important to not confuse CEO calibre/performance and their attitude to the board. We have all seen some cases of highly dominant CEOs with weak boards who deliver outstanding results for their shareholders. However, there are a lot more cases where a CEO-dominated board can be the root cause of corporate failures and serious under-performance going un-checked for too long due to the board being effectively powerless.

CEO-managing-the-board

This is a variation of the CEO dominated board category that is a lot more subtle and harder to identify. This is where the CEO and executive team very carefully “manage the board”. While the CEO and executive team are prepared to grudgingly accept challenge, debate and oversight from the NEDs on the board, deep down they believe they “genuinely know better”, understand that they need to let the NEDs do their job but ultimately feel the NEDs have no serious value to add ( even when they know they have sharp NEDs who could add serious value ! ). As a result of this, the CEO and executive teams don’t view the board as a genuine team in its own right that adds serious value where they partner closely with the NEDs– balancing outstanding levels of high-quality challenge and debate with the NEDs being enabled and encouraged to add serious strategic value and enhance the thinking of the executive team. This manifests itself very often in the CEO not engaging the NEDs to work with the exec team on strategy and asking for the NEDs’ help when serious performance issues start to emerge in a particular area. Clearly there are cases where the CEO will listen to the NEDs when something very serious is highlighted but in general the CEO and executive team see board meetings as a necessary evil and while doing what’s professionally expected of them in terms of board reporting etc., they effectively want to get in, get out, get their decisions and strategies approved and allow them to get back to running the business. Every time I see this situation, I am always dismayed as this undermines the capability of the board to add serious value, is very dis-empowering to the NEDs on the board, reduces the quality of major decision-making and strategy formation and ultimately is letting down the shareholders.

“Mini-board” within a board

This is quite a serious type of problematic board and a more common problem than what a lot of people realise. This is the case where there is effectively a “mini-board” that exists that comprises the CEO, the board chair and sometimes a trusted long-serving non-executive director or shareholder/investor nominee director closely aligned to the CEO. In this model, this mini-board calls the shots and makes the decisions, often actually physically meeting or have conference calls in advance of the main board meeting in which they literally conduct the planned board meeting, make the major decisions and where needed, agree an appropriate strategy to “get these decisions through the main board”.The board meeting then happens and while some of the executive and non-executive board members believe they are actually having a board meeting, in reality it is more akin to a charade where the mini-board members telepathically linked around the table carefully orchestrate the board meeting to arrive at “their decisions”. To say that this is extremely dis-respectful and disempowering to all of the board members not in the “mini-board” would be an understatement. This is not a healthy situation for an organisation and can create a special type of “group-think problem” whereby the “mini-board” can lose their way on a critical issue. A lot of these boards can often go quite stale as well as the “mini-board” is very careful about refreshing the board with sharp NEDs who would spot this type of problem a mile off and cause trouble for the “mini-board”.

“All of the NEDs have gone native” board

This is an interesting type of problematic board which I have seen from time to time and often occurs in cases where the board composition has remained static for quite a long time and there has been no refreshing or structured succession planning for long-serving board members. In this scenario, the NEDs on the board have effectively gone native with the CEO and executive team and no longer demonstrate the required levels of “independence of mind” that are needed for a vibrant independent NED on a board. In many cases, the NEDs don’t fully realise this and this often only surfaces in the case of an external board evaluation.This is precisely the scenario that the nine-year rule for non-executive directors in the UK corporate governance code ( and similar provisions in other national governance codes ) is designed to help avoid. In this scenario, I have seen some serious group-think problems whereby the quality of challenge, debate and strategic thinking is seriously curtailed, the oversight of the executive team is weakened and the board are not capable of performing at a high-level on behalf of their shareholders.

Board chair/non-executive controlling board

This is in many respects the opposite of the preceding cases whereby the board chair and non-executive directors are the dominant force on the board. While in publicly listed company boards and non-profit charity boards, you would have a majority of non-executive directors, the problem with this type of problematic board is that it is un-balanced with the CEO and executive team in a very “sub-servient passive type mode” and effectively dictated to and in some extreme cases micro-managed by the board.Often in these scenarios you can find a board chair who is either deliberately or inadvertently crossing the line into a quasi executive-chairman type role sometimes supported by NEDs with strong executive backgrounds who miss being in the CEO hot-seat and not afraid to give the CEO “helpful advice”. Sometimes this scenario can develop with first-time CEOs, a current executive who has just been promoted internally to the CEO role or an existing CEO who has just taken on the role of a CEO in a far larger organisation and is intimidated by the reputations and CVs of the board chair and NEDs around the boardroom table. Either way, it can be very undermining of the CEO and executive team, can constrain serious strategic thinking and ambitions by the executive team who are continually looking over their shoulders in terms of “pleasing the board” and shaping their thinking to “the board’s perceived wisdom”.

Over-arching shareholder controlling/impacting the board

This is a less common scenario whereby a minority shareholder exerts a dis-proportionate influence on the board’s functioning and effectiveness. Sometimes it’s a large minority shareholder who may have been one of the original founding shareholders or an early investor. A common pattern in these cases is that the board chair can be either a formal nominee of this shareholder or is de facto aligned to this particular shareholder with the result that the board’s leadership of the board can be unduly influenced by one particular shareholder. A core principle of corporate governance is that the board should act at all times in the best interests of the company and shareholders taken as a whole and not in the best interests of one or a sub-set of shareholders. There are clearly exceptions to this such as a private-equity backed company majority owned by the PE firm but I have seen many situations where this principle is blatantly violated and one or a sub-set of shareholders either explicitly or more subtly try to control the functioning and decision-making of the board. This is not good for a company and this scenario is often the cause of serious board and shareholder disputes when either the other shareholders and/or executive team confront this and cause this to be brought out in the open.

Under-powered board

This is quite a common scenario whereby the NEDs on the board are simply not strong enough to add serious value to the organisation. In many cases, board chairs and CEOs need to take a lot of the responsibility for not setting the bar high enough in terms of ensuring a vibrant diverse mix of high-calibre NEDs bringing a great combination of industry and sector expertise and general executive skillsets to the table that can add significant value to the decision-making and strategic capability of the CEO and executive team. I have seen many cases where CEOs have very deliberately picked friends and former colleagues from the “old boys network” who they know would not “rock the boat” in terms of serious challenge and debate and would tick the box of having so many NEDs on the board. In board evaluations, I have often heard CEOs complaining about the “low value being added by their NEDs” that they actually selected originally ! This is a very un-healthy situation for shareholders and stakeholders who in many cases don’t fully appreciate how under-powered their board is and how little value in reality the board adds to the organisation.

Going-through-the motions board

This is an interesting problematic scenario where you have on the surface all the right ingredients for a strong board but in reality for a host of different factors, the board is simply going through the motions as a functioning board adding very little value beyond oversight ( and in some cases not even doing this properly ) . Some of the factors which can cause this are ;

- A genuinely tired board where several members are doing the bare minimum and have effectively “checked out”

- A disillusioned board whereby for a number of different reasons such as a difficult few years for the organisation, the aftermath of a very serious crisis or a prolonged struggle with a problematic CEO/executive team, the board has lost its spark

- A board that lost its “fire-in-the-belly” and has become stale. In many cases, the board chair has struggled to demonstrate strong leadership and did not refresh the board and improve diversity at key stages

- A board where all trust has broken down for various reasons, executive and non-executive board members are barely co-operating, significant factions exist in the board and while the board is functioning from a black-and-white corporate governance perspective, it is not an effective board adding serious value

- A board in which the overall work-ethic, commitment and performance culture of the board and the NEDs has been allowed to slip to a low level. In some cases, this can be a manifestation of an “over-boarding problem” whereby the NEDs are not devoting sufficient quality time to this specific board.

In some respects, this can be the most serious of the problematic board categories as it can comprise a very in-effective board that is doing a great dis-service to the shareholders and stakeholders of the organisation. In some cases where an organisation or company is either seriously plateauing or is on a downward slide, the root cause sometimes can be a poor quality board that is seriously struggling or just drifting along.

Summary

For the shareholders, employees and stakeholders of a company or organisation looking on at their board of directors, it can be very difficult to truly understand what’s happening below the surface of what’s visible and what’s really happening within the board. In my experience, the vast majority of issues and problems with boards are not strictly corporate governance related, they are instead related to the “people equation of the board” and the complexities of how each member of the board, executive and non-executive, behave both individually and collectively.I cannot stress enough the critical responsibility entrusted to the board chair to ensure that the board excels on behalf of shareholders, employees and stakeholders and avoids the type of problematic boards outlined here. In every board, both the board chair and CEO have a critical responsibility to avoid these problematic board types and ensure that

- The board has a genuinely diverse composition of high-calibre independent non-executive directors who have a strong work ethic, are genuinely committed to the organisation and can add serious value to the executive team and the organisation overall

- The CEO and executive team demonstrate the highest levels of accountability, behaviours, integrity and respect for the board and the NEDs

- There is a genuine partnership model between the executive and non-executive directors which balances the highest levels of challenge, debate and oversight with the NEDs adding serious value in supporting the executive team

- The continued tenure of every single board member, irrespective of their experience/stature/track record is regularly reviewed and if they are not making a genuine high-value contribution to the board that they will be replaced by someone who will

- There is a genuine performance culture within the board team and commitment to excel on behalf of the shareholders, employees and stakeholders who have entrusted the board with the stewardship responsibility for the organisation

Kieran Moynihan is the managing partner of Board Excellence ( https://board-excellence.com) – supporting boards & directors in Ireland, UK and internationally excel in effectiveness, performance and corporate governance.

Think your business could benefit from our services and expertise? Get in touch today to see how we can support your board excel for its shareholders, employees and stakeholders.

.